Lessons from George and Horace: The Woodcraft Trio

3rd Jun 2014

We love hearing from our friends and customers, of course. Some days, though, it feels to us like everyone is looking for The Knife, that one do-it-all blade that can take on everything from kitchen chores to end-of-the-world survival.

That's fine, as far as it goes -- there's nothing wrong with nurturing the skills required to survive if limited to a single blade -- but as much as we hate to bear bad news, we have to tell you: There's no such knife.

No one knows that better than people who spend time in the wild places. And when today's outdoorsmen talk of the tools they take with them into the woods, often they'll invoke the names Nessmuk and Kephart.

In the 1880s, "Nessmuk" was the by-line of stories penned by George Washington Sears for Forest and Stream magazine. The Massachusetts native wrote of camping and paddling in the Adirondacks of upstate New York. His 1884 landmark book, Woodcraft, has never gone out of print.

Horace Kephart followed Nessmuk chronologically and, in many ways, philosophically. Also a contributor to Forest and Stream, his articles were gathered into Camping and Woodcraft, first published in 1906. Kephart was born a Pennsylvanian, but he's best known for writing of his life in and love of the Smokies of western North Carolina. He was an early and avid proponent of establishing Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

Nessmuk and Kephart are read and revered to this day, arguably the old and new testaments of life in the woods. Both men espoused respect for the land and pioneered what we now refer to as "ultralight" camping.

Each man's legacy also includes a knife pattern that bears his name. Beyond those distinctive blades (which we'll talk more about in the next KnivesShipFree Blog post), what we should remember most are the "systems" of edged tools that accompanied them on their wilderness forays over a century ago.

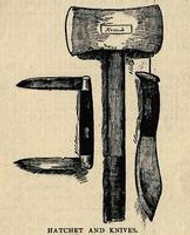

Nessmuk was a woodsman, not a survivalist. He was bent on thriving in wild places, writing of a sensible trio of tools: a hatchet, a simple jackknife and a fixed-blade knife of his own design. Here's how he described each part of his woodcraft system:

"The hatchet and knives...will be found to fill the bill satisfactorily so far as cutlery may be required. Each is good and useful of its kind, the hatchet especially, being the best model I have ever found for a 'double-barreled' pocket-axe."

"Before I was a dozen years old I came to realize that a light hatchet was a sine qua non in woodcraft, and I also found it a most difficult thing to get. ... I had hunted twelve years before I caught up with the pocket-axe I was looking for."

"A word as to knife, or knives. These are of prime necessity, and should be of the best, both as to shape and temper. The 'bowies' and 'hunting knives' usually kept on sale, are thick, clumsy affairs, with a sort of ridge along the middle of the blade, murderous looking, but of little use; rather fitted to adorn a dime novel or the belt of 'Billy the Kid,' than the outfit of the hunter. The one shown...is thin in the blade, and handy for skinning, cutting meat, or eating with. The strong double-bladed pocket knife is the best model I have yet found, and, in connection with the sheath knife, is all sufficient for camp use."

(We always get a kick out of that last passage -- apparently, "tacticool" knives were as prevalent in Nessmuk's 19th-century world as they are today.)

Thirty-three years later, Kephart echoed his predecessor:

"A woodsman should carry a hatchet, and he should be as critical in selecting it as in buying a gun. The notion that a heavy hunting knife can do the work of a hatchet is a delusion. When it comes to cleaving carcasses, chopping kindling, blazing thick-barked trees, driving tent pegs or trap stakes, and keeping up a bivouac fire, the knife never was made that will compare with a good tomahawk."

"The conventional hunting knife is, or was until recently, of the familiar dime-novel pattern invented by Colonel Bowie. It is too thick and clumsy to whittle with, much too thick for a good skinning knife, and too sharply pointed to cook and eat with. It is always tempered too hard.

When put to the rough service for which it is supposed to be intended, as in cutting through the ossified false ribs of an old buck, it is an even bet that out will come a nick as big as a saw-tooth -- and Sheridan forty miles from a grindstone!"

"The jackknife has one stout blade equal to whittling seasoned hickory, and two small blades, of which one is ground thin for such surgery as you may have to perform (keep it clean). Beware of combination knives; they may be passable corkscrews and can openers, but that is about all."

That's great stuff, isn't it? It's nothing short of essential, elemental woodcraft. But using Nessmuk's and Kephart's philosophies only as a springboard for nostalgia, trying to mimic these outdoorsmen's tools, risks missing the point.

Oh, sure, plunging headlong into the wilds equipped with modern copies of Kephart- and Nessmuk-pattern fixed-blades, along with duplicates of their axes and jackknives wouldn't be a bad place to start -- but it's only a start.

When we read more carefully the writings of Nessmuk and Kephart, we find that each man arrived at his now-familiar system of tools through trial and error. Why shouldn't we?

They found tools that worked by working the tools they had. We're willing to bet that had George and Horace lived longer, practical experience would've shaped their choices even further.

And so, it seems to us, we can draw two fundamental lessons about edged tools from these woodcraft legends: have a system and work the system. With that mindset, we can get past mere imitation.

Looking for a latter-day example of what we're talking about? Mike Stewart of Bark River Knives, several years ago, offered this take on what he calls his "bushcraft set":

"I like to have...a four-inch blade and a smaller knife (fixed or folder) for fine work, and either a mini-axe or Golok. With that set, there isn't much that can't be accomplished -- from basic camp chores to shelter building.

"While I agree with the concept of the three-tool set (like Sears), I don't agree with his selection of cutting tools. In practice, I actually expand the three-tool set into four by carrying a small fixed-blade and a folder in my pocket. I can't imagine not having a folder in my pocket at all times."

See, it's not heresy to differ with Kephart or to stray from Nessmuk's trio. In fact, we contend that challenging these standards -- based on personal experience -- is the whole idea.

In our next post, we're going to stick with George and Horace, taking a closer look at the classic fixed-blade knife patterns associated with them. So stay tuned -- you might just be in for a surprise or two.